An artist who is best known for producing work wrought with tension, contradiction, and the grotesque, Alfonso Ossorio experienced an early life filled with migration and displacement that served as a breeding ground for internal struggles he would later face as an adult.

Ossorio was born on August 2, 1916 in Manila, Philippines to Maria Paz Yangco and Miguel José Ossorio, one of six sons. Before the age of ten, Ossorio was sent to boarding school in England, never returning to the Philippines until more than twenty years later in 1950. His early childhood and teenage years were filled with continuous movement, from St. Richard’s Catholic boarding school in Worcestershire, England to the Benedictine Portsmouth Priory in Rhode Island before settling in Cambridge, Massachusetts for four years where he completed his Fine Arts degree at Harvard University. Post-degree, Ossorio lived in various cities such as Taos, New Mexico, Camp Ellis, Illinois and New York City before settling into his sprawling estate in the East Hamptons called The Creeks where he would live until his death in 1990.

The 2016 Salcedo Private View show Meditations + Mediations: The Art of Alfonso Ossorio chronicles the biographical nature of Ossorio’s work through three of his most telling periods as an artist—the 1930’s surrealist drawings, the 50’s “Victorias Paintings” and the 60’s “Congregations,” strung together by an underlying concept of the merging of art and life. While his materials and forms changed, Ossorio’s art was continually engaged with the mysteries inextricably connected to his own life such as issues of identity, sexuality and religion.

PROVENANCE Alfonso Ossorio, East Hampton, NY Collection of Gisella Beker, East Hampton, NY (acquired directly from the artist, 1970s) Collection of Brian Beker (son of Gisella Beker), Los Angeles, CA (acquired by inheritance from above) Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

EXHIBITION & PUBLICATION HISTORY

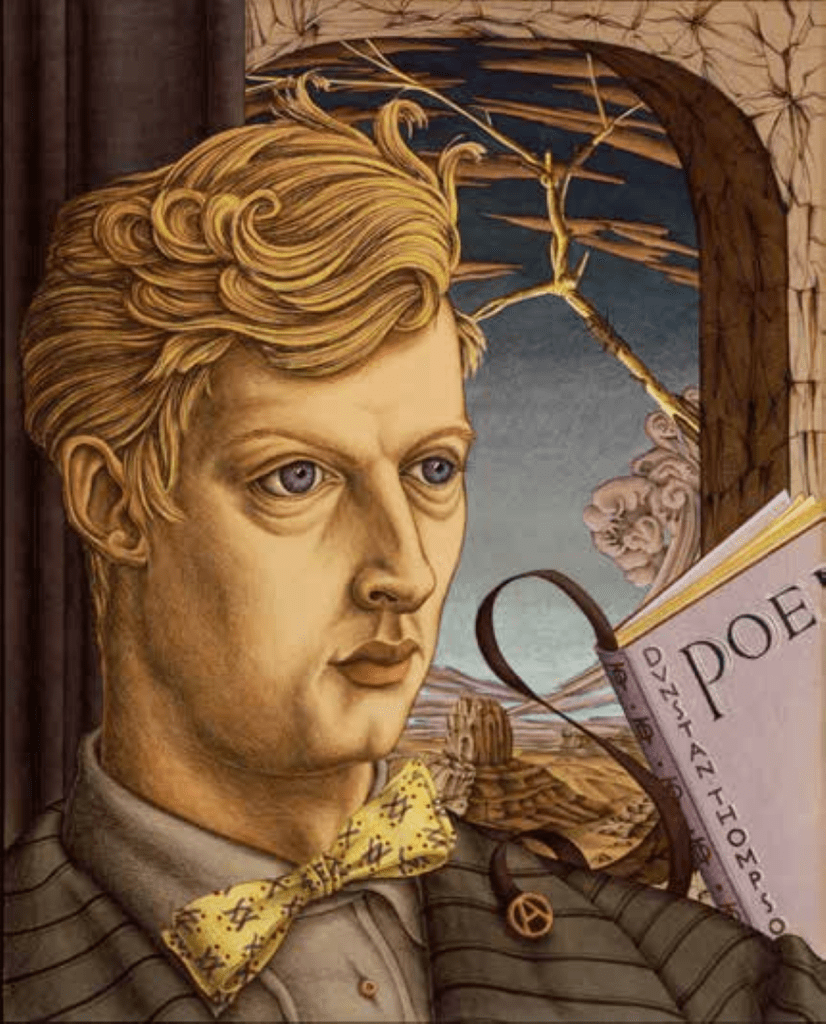

Alfonso Ossorio: Paintings and Drawings, Wakefield Gallery, New York, NY, February 23-March 9, 1943 Boswell, Helen, “Ossorio at Wakefield Gallery,” Art Digest, 1943 Dustan Thompson mentioned and illustrated in review Friedman, B.H., Alfonso Ossorio. New York: Harry F. Abrams, 1972 Illustrated in black and white on page 24, plate 9

COURTESY OF MICHAEL ROSENFELD GALLERY, LLC, NEW YORK, NY

Over two summers in the early 1930s, Ossorio trained in the workshop of Eric Gill, a wood engraver who was known for his craftsmanship in woodcutting and engraving. A prolific writer, Gill authored several books and essays that spoke of his primary objective as a craftsman—that of the assimilation of art and life. He wrote in 1936, “It all goes together—industrialism and the leisure state, the potentially contemplative prostituted to the active, the sacred to the profane.” While early in his career, this idea of integration would be an abiding theme in Ossorio’s art.

PROVENANCE Private collection Important Philippine Art, Salcedo Auctions, 19 September 2015, Lot 140 Private collection, Manila

By 1934, Ossorio enrolled in Harvard University working towards a Fine Arts degree. Aside from classical training, he also explored an early curiosity into the primitive arts through frequent trips to the Peabody Museum. During his time there, he wrote his thesis “Spiritual Influences on the Visual Image of Christ.” An investigation into the stylistic evolution of the way religious iconography depicted Christ, it examined how “variations in Christian religious thought” was manifested in art. This scholarly effort was an indication of his interest in linking culture and tradition into the evolution of the visual.

In 1939, he met divorcee Bridget Hubrecht whom he married in 1941 and lived with in Taos, New Mexico. Around the same time, Betty Parsons saw Ossorio’s work and booked him for his first one-man show in New York that was held in November 1941. A month after the exhibit closed, Ossorio and his new wife separated. While waiting for the call for service in the army in which he had enlisted, Ossorio was hit by a taxi in New York, breaking his leg. As he was recuperating, Parsons gave him a second show in 1943 in the Wakefield Gallery where he presented portraits mostly done in the early 1940s. Helen Boswell discussed the show in Art Digest, “Growing out of the winding tendrils of the Surrealist School, Ossorio arranges accurate likenesses which reveal considerable insight and full fashioned craftsmanship against fantastic backgrounds.” The portraits mixed what Boswell called the “classic precision of Germanic old masters” and a predilection towards Surrealism, showing dream-like states and introspective dispositions. In Dunstan Thompson, 1942, Ossorio paints friend and poet, Thompson against the backdrop of a window to a barren desert, a swirl of pink clouds sweeping upward to the azure sky, the dreamlike state finding commonality with the Surrealist movement that had recently moved to New York from Europe.

PROVENANCE Alfonso Ossorio, East Hampton, NY Machel Tapié, Paris, France Private collection, Paris, France Piasa, Paris France, 17 June 2009, Lot 4 Private collection, New York City Private collection, Manila

Also in 1943, Ossorio entered the US army as a medical illustrator. While stationed at Camp Ellis in Illinois, he was accidentally injected with distilled water for the treatment of his injured leg. Time spent at the Mayo General Hospital allowed him to become familiar with medical drawing, where he sketched scenes of arterio-vascular and neurological surgery—motifs showing the inward and outward on one plane which he would explore further in his “Victorias Paintings” a few years later.

In early 1949, Ossorio purchased his first Jackson Pollock painting, No. 5, 1948, from a Betty Parsons Gallery show. Ossorio soon met Pollock himself, and Pollock’s wife Lee Krasner after. From this point on, Ossorio, Pollock, and Krasner forged a lifelong friendship. Pollock later encouraged Ossorio to meet with Jean Dubuffet, a French artist and leading proponent of Art Brut, a movement which Dubuffet characterized as “works carried out by persons devoid of any artistic culture, works in which, as opposed to the practice among intellectuals,” Ossorio became so fascinated with Dubuffet’s collection that in 1951, he housed all 1,200 pieces in The Creeks for ten years.

The relationships that Ossorio forged with both Pollock and Dubuffet proved to be a dominant factor in his stylistic shift. He stated, “The influences of Dubuffet, Still and Pollock on my life have common roots: I had always been more interested in pre-Renaissance painting, in primitive art and in all forms of Oriental art than in the European tradition that prevailed between 1400 and our own time. And I was mesmerized by the way each of these painters revolted against the Western tradition and dealt with post-cubist space.” With his trip to his family’s sugar plantation in Victorias, Negros Occidental approaching, the influences of Art Brut, Abstract Expressionism and the primitive arts would result in an abstract style of more visceral strokes, providing an aesthetic for the psychological tension that he had already been exploring during his Surrealist years.

PROVENANCE Acquired from the artist by Alice Dowling By descent to a previous owner Acquired from the above by the previous owner First Open: Summer Edition (Post-War and Contemporary Art), Christies New York, 24 July 2014, Lot 129 Important Philippine Art, Salcedo Auctions, 7 March 2015, Lot 46 Private collection, Manila

In early 1950, almost thirty years since he left, Ossorio returned to his hometown to work on a commission for a new church, St. Joseph the Worker, which his family was building within their sugar plantation. In preparation for his Philippine trip, and as research for his mural, Ossorio read Nandor Fodor’s book, The Trauma of Childbirth. Revolving around the idea that every infant experiences trauma upon birth, the book tackles issues of claustrophobia, insomnia, and nightmares that find their onset in the early months of life and may continue unconsciously onto the later years. In Fodor’s words, “After nine months of peaceful development, the human child is forced into a strange world by cataclysmic muscular convulsions which, like an earthquake, shake its abode to the very foundations.” The concept of a return to womb, coupled with the timing of the trip, is telling of the anticipation of emotions and fears that Ossorio was facing in preparation for Victorias. Through this experience, Ossorio was forced to confront the realities of post-war Philippines and the emotional tension of returning to a birthplace that had become foreign to him.

While working on the mural during the ten-month trip, Ossorio painted abstract and figural paintings using a new “wax-resist” technique which he adapted from French Surrealist Victor Brauner – the pieces that are now collectively referred to as the “Victorias Paintings.” The “Victorias Paintings” were a convergence of the traditional and the primitive, a unity of artistic influences and personal struggles, deliberate figures with unintentional designs. Ossorio biographer B.H. Friedman said, “It is impossible to explain categorically why one period in an artist’s life is more fecund than another. Though Ossorio has almost always been productive, there ha[d] never been a time when he so rapidly produced so much of his best work as during these months.”

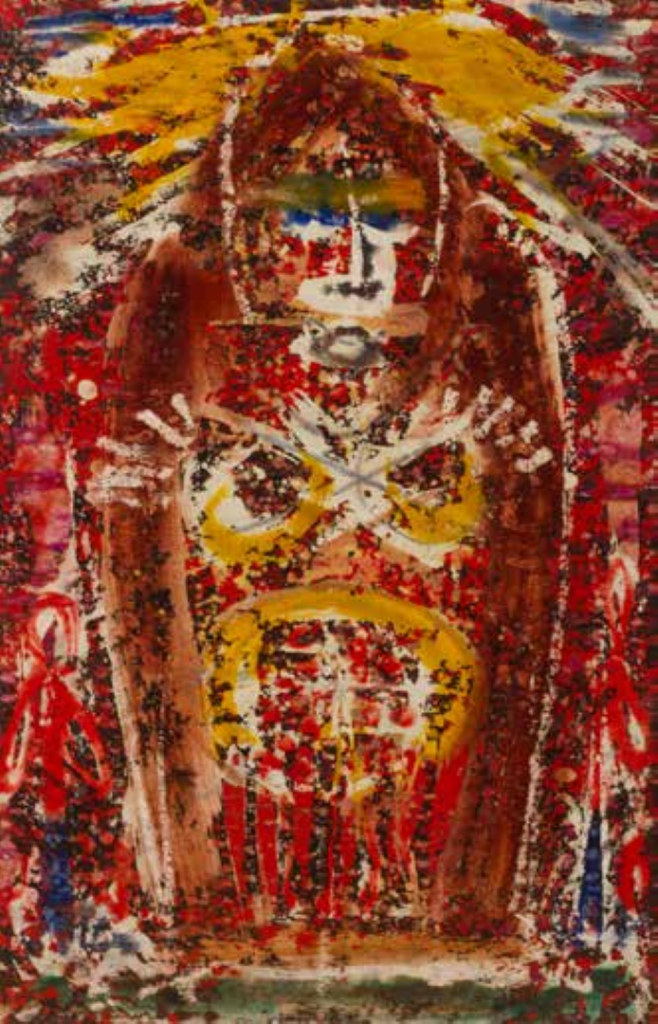

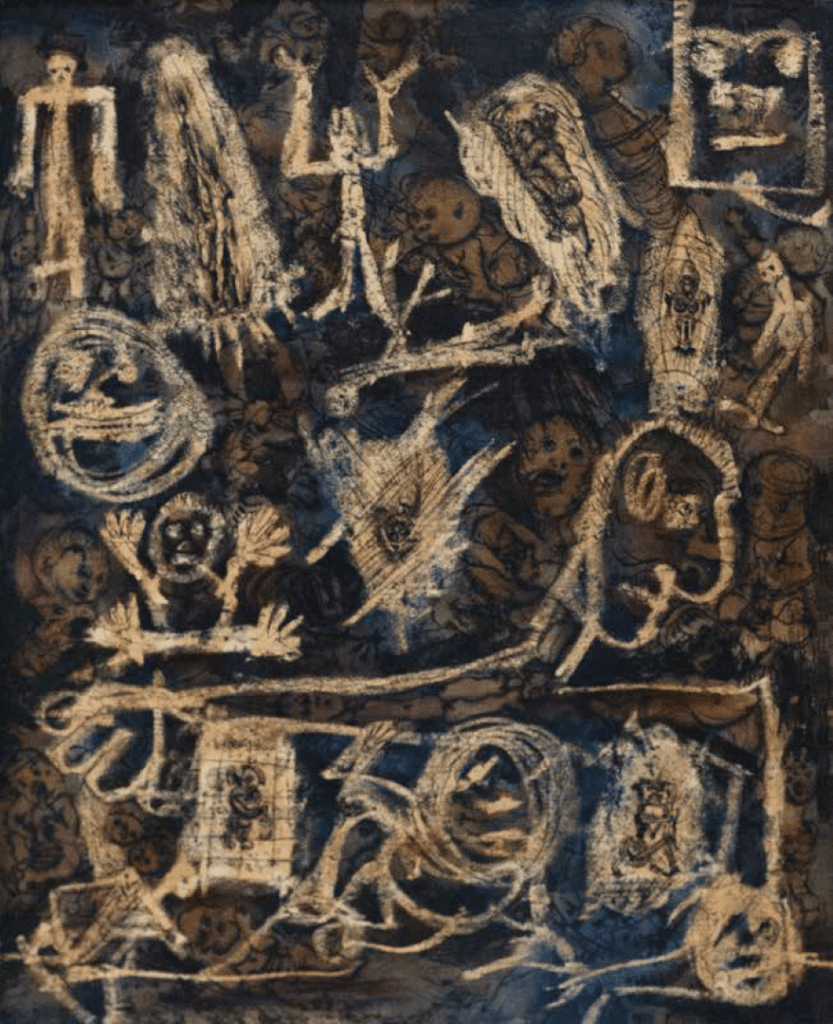

The “Victorias Paintings” were the results born from Ossorio’s early inquiry in his Harvard thesis into the relationship between the changing images of Christ and movements within society. The images he created, the interpretations of the Eucharist, death, and the Crucifixion have to be seen within the context of his personal influences and then current issues in order to be fully translated. In a 1967 Art in America interview by Francine du Plessix, the writer asked Ossorio how he felt about the frequently oversimplified analyses of his work. Ossorio replied, “False clarity, the segregation of or impoverishment of any aspect of organic existence, can only produce monsters…No larger unity can exist without enhancing the vitality of the particular…” Ossorio’s inner torment was revealed in the “Victorias Paintings,” a reinvention of his artistic style that would prove to be most the most significant in his ouevre. In St. Maria Goretti and Head (Veronica), both 1950, we see his exploration into the primitivism of religious figures through flattened dimensionality and crude figurations. St. Maria Goretti, the Italian martyr is portrayed in a macabre scene, engulfed in a blanket of red, scratches of ochre replacing her saintly halo. Head (Veronica) on the other hand references the mystery behind the “veil of Veronica,” depicting the imprint of Christ’s face, with slanted eyes and downturned lips, piercing through the texture of the crumpled sheet (Ossorio often used paper scraps while in Victorias, for lack of material). In both cases, the figures are defined by their agony rather than form. Most encapsulating the idea of distinctive parts conjoined to make a whole is We Are Many. Done during the same ten month trip, the pivotal piece shows Ossorio’s horror vacui through dozens of infants, faces and almost hieroglyphic-like bodies, strung together to create a cohesive whole.

PROVENANCE Michel Tapié, Paris Private collection, Paris Art Contemporain, Millon Maison de Ventes Aux Encheres, Paris, France, 1 April 2015, Lot 8 Private collection, Manila

After the Victorias trip, Ossorio continued experimenting with the wax-resist techniques. In the large Fourth of July, done in December of 1954, the presence of red, white and blue are anchors to an increasing influence of Abstract Expressionism, (aside from Pollock, he also mingled with leading artists of the movement Barnett Newmann and Clyfford Still), with more defined, confident lines commanding an explosion of threatening abstract contours. In Composition, 1956, Ossorio plays with the physicality of the artwork, translating the same visceral strokes into an oil on canvas medium, which in this particular case, was completely removed from the objective. Untitled, 1960, shows Ossorio’s continued preoccupation with the techniques he had explored during the Victorias trip some ten years earlier, with an outstretched horizontal body centered on a torso with anatomical renderings of ribs and vertebrae.

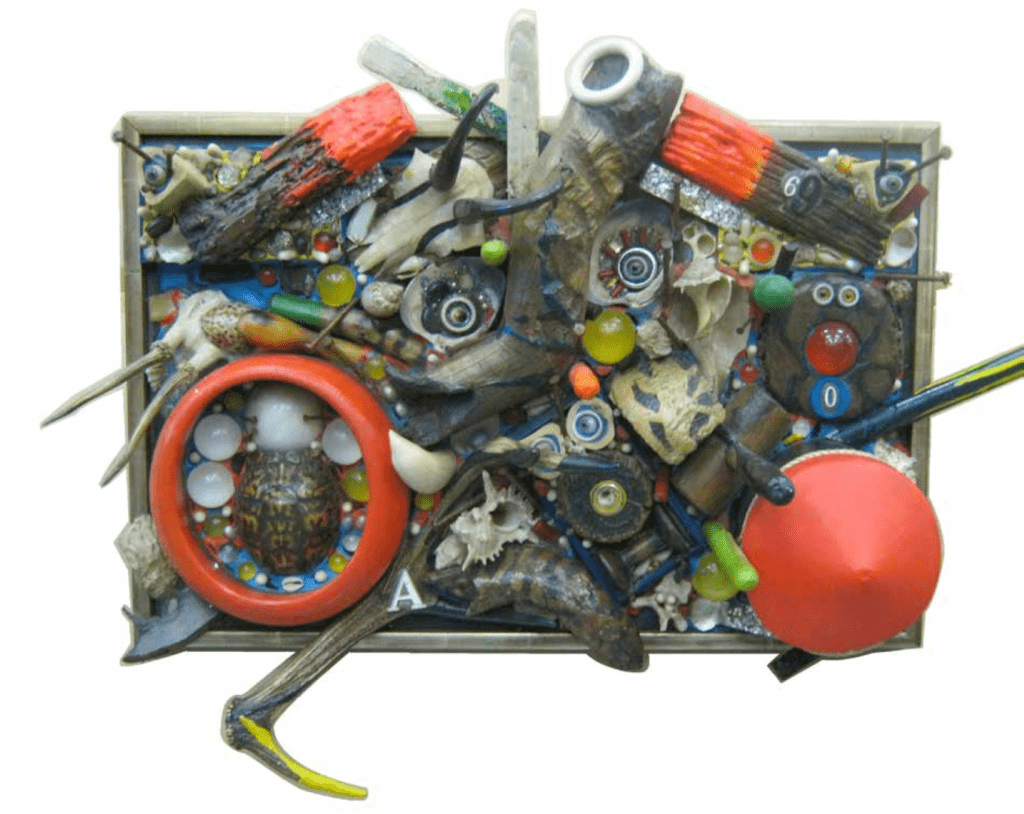

In the 1960s, Ossorio began experimenting with assemblage. Dubbing them his “congregations,” the curator of modern art at the Fogg Art Museum, Harvard noted that the new style “cannot be squared with Pollock’s skeins and Dubuffet’s encrustations; they speak instead of fetishes, reliquaries, and icons. They are both catholic and Catholic…” Ossorio’s congregations, as the name suggests, combine found objects: shells, glass beads, bone, rope, brass rings, ceramic and the like, bound together on panel. In the arresting, Fluxus, 1969, his use of natural and biological material such as tortoise shell, bone horn, juxtaposed against the synthetic glass eyes, ceramic and nails retain the same frenetic energy his previous work, but with a newfound tactility. Friedman noted, Ossorio’s use of waste was reflective of his affinity towards “’seconds,’ rejects, remnants” that he purposefully collected to become the foundation of his art. “Nothing is found,” Friedman continued, “everything is sought.” By transforming the old into new and combining parts into a whole, Ossorio evolved the same ideas of integration he had been enamored with since the beginning of his career into a new medium.

PROVENANCE Father Pierre Riches, Italy (acquired directly from the artist) Galleria Lorcan O’Neill, Rome, Italy James Barron Art, South Kent, CT Private collection, Los Angeles, CA The Holiday Sale, Salcedo Auctions, 28 November 2015, Lot 223 Private collection, Manila

Towards the latter part of the twentieth century, some art historians attributed Ossorio to being one of the forefathers of the Pop Art movement in America, an association he disagreed with. The difference he saw was in the transparency of the message. He said, “My work, if anything, is the opposite. It is ritualistic and meditative. It is, if you want, religious. There is a sense in which religion means ‘to tie together,’ and that is also my sense of what art is all about: to disclose unity.”

PROVENANCE Cordier & Ekstrom, New York Private collection, New York Art Contemporain, Christie’s Paris, 4-5 June 2014, Lot 137 Private collection, Manila

This article is an excerpt from Spirituality and the Folk in Alfonso Ossorio’s Victorias Paintings Graduate Thesis, Pratt Institute, 2015 by Regina Marie S. Aquino

Salcedo Private View acknowledges the research assistance and advice of the Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York in the organization of this exhibition.

Footnotes

B.H. Friedman, Alfonso Ossorio (New York: H.N. Abrams, 1972), 13. Wolfe, Judith, ed. Alfonso Ossorio 1940–1980 (East Hampton: Guild Hall Museum, 1980), 5. Eric Gill, It All Goes Together: Selected Essays (New York: The Devin-Adair Company, 1944), 56. Friedman, Alfonso Ossorio, 13. Wolfe, 18 Wolfe, 18 Friedman, Alfonso Ossorio, 21 Friedman, Alfonso Ossorio, 21. Ibid. Ibid. Ibid, 22.

Helen Boswell, “Fifty-Seventh Street in Review,” Art Digest Vol 17. No. 11 (March 1,1943): 20-21. Friedman, Alfonso Ossorio, 25 Ibid, 26. Ibid. Friedman, Alfonso Ossorio, 33. B.H. Friedman, Jackson Pollock: Energy Made Visible (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1972), 131. Michel Thevoz, The Art Brut Collection Laussane (Zurich: Swiss Institute for Art Research, 2001), 7. Du Plessix, Francine, “Ossorio the Magnificent.” Art in America Vol. 55 (March-April 1976, 60. Ibid. Francis V. O’Connor, “Alfonso Ossorio’s Expressionist Paintings on Paper,” in Alfonso Ossorio: The Child Returns, ed. Halley K. Harrisburg (New York: Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, 1998), 2. Friedman, Alfonso Ossorio, 41. du Plessix, 63. Harry Cooper, “Introduction,” Alfonso Ossorio: Masterworks from the Collection of the Robert U. Ossorio Foundation, Halley Harrisburg, ed. (New York: Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, 2007), 8. Friedman, Alfonso Ossorio, 84. Ibid. du Plessix, 61.